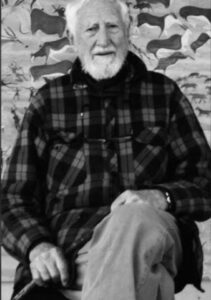

In the weeks since Bill’s passing at the age of almost 101, many of us who knew him, or knew of him, would have pondered about a life so long, and so well spent. What is its meaning? And how should it be spent?

He has fittingly been described as “Man of the Mountains”. Until his passing he was also South Africa’s oldest surviving qualified forester. He had many interests, in conservation, science, gardening, and service to community.

Among his many passions, none seemed to capture his spirit more than his love for flyfishing, more specifically flyfishing for trout. I had the privilege of witnessing this firsthand. It is difficult for me to pinpoint the moment I fully appreciated his skill and immersion in his craft.

My dad and I often fished with Bill. Joining him on a river usually meant trying to keep up with his lanky stride and animated stories, and bush-bashing through Nchichi bushes along the riverbank to find his secret fishing spots. He caught many trout. We caught a few. Often, we simply followed along the riverbank behind him, watching his effortless technique. We tried to emulate his high-sticking, punchy casts into the rapids. His fly -a simple, nondescript pattern-tumbled naturally between the rocks and eddies. He worked the tip of his rod in a way that imparted just enough natural movement to bring a strike, almost every cast. Those days were pure delight, drifting in and out of my boyhood memory.

One spring we set out on a hiking-fishing trip to the upper Pholela. We explored a seldom-fished, cascading side stream, visited caves with ancient Bushman paintings, and cooled off in deep pools in the heat of the day. Absorbed in our fishy pursuits, we didn’t notice the fast-approaching storm rolling down from Hodgsons Peak. Fierce wind whipped around us, the rain fell in sheets and the thunder boomed and echoed across the valley while we took whatever shelter we could in a shallow overhanging cave. For what seemed like hours Bill kept us entertained and captivated with stories of his childhood, his travels and of his time in the ‘berg. And of course, about trout fishing. As impatient as I was for the storm to pass, it was evident even to me as a boy that this was important stuff and that I should listen. I learned a lot that day.

Eventually the main stormfront passed down the valley. The moon poked through the clouds, shimmering on the surface of the river to reveal trout rising everywhere. We strung our rods back together and fished on into the night, the path lit occasionally by a distant lightning strike. We must have caught well over 200 trout that day. Their size meant little. The method mattered more. Most of them were small, each one more speckled and beautiful than the last. We kept a few for Bill’s smoker. The rest were returned, hopefully to populate the lower reaches of the river as they ventured downstream through the summer.

Sometime in the late 1970’s I had the chance, the privilege, to fish with Bill on an otherwise inaccessible section of the middle reaches of Pholela. Around mid-morning, we paused for tea and sandwiches on the riverbank and swapped stories and talked flies. From his old canvas bag Bill produced a small handheld vice, scraps of dull fur and thread, a bobbin and a small, battered pair of scissors. He quickly whipped together a couple of nymphs, lightly weighted with strips of wine bottle lead.

As a young newbie fly tier -then naively experimenting with an array of exotic materials, bright colours, flashy Mylar and highly intricate, imitative patterns- the fly that Bill produced from his hand vice was confronting in its simplicity. He finished it off with a couple of half hitches and then roughed it up under his boot, grinding mud and rough disorder into the hairs.

Later that morning, I watched him land a three-and-a-half pound Pholela rainbow on that battered fly, which by then had been frayed and teased up by the teeth of several smaller fish.

Over the last few weeks that Fly has drifted back into my consciousness. I just wish I had kept an original. I have tried several times to recreate it without success, which says so much about how simple and suggestive it was, and about how out of practice I am at the tying bench.

Its simplicity was elusive – a study in restraint. If you’ve ever seen a properly tied Kite’s Imperial, or a Sawyer’s Killer Bug, you will know about elegant simplicity. Some tiers have that ability to craft fly patterns that just work. They catch trout. They use few materials. And they tie them quickly, with minimal fuss and embellishment. Frugal – some might even say Scottish.

Bill’s nymph was extremely simple and was tied with little more than hare’s fur, bound with sewing thread, and wine bottle lead for weighting. He formed the wingcase in a way I had not seen before. A bit like the doubled-back wing case of the Kite’s Imperial. But simple. Dead simple. Yellow sewing thread for ribbing. Not much else. A tuft of wispy rabbit guard hairs for the tail. The body was wound from several long, course strands taken from the hare’s back, or from somewhere on the animal where the hair is long, course and strong enough to be wound around the hook shank, not the way we usually dub with soft, fine rabbit fur.

The main challenge was the fur itself. Bill used hair from one of those large red midland hares commonly known as a Natal Red Rock Hare, or “intenesha” in isiZulu. The red rock hare is larger than your typical rabbit, it has back hair that is long enough to be used as an abdomen wrap, or wing case, rather than as a traditional soft dubbing. My Dad joked that Bill probably shot it or hit it with his work bakkie, but I have no proof or direct knowledge of its origin, only that it was different to common rabbit fur that you can buy in a fly-fishing shop.

It is hard to capture that fly in words. I will continue to try and conjure an acceptable replica, but perhaps some things are meant to remain a life lesson without clear instructions. And maybe that’s where it should be left.

Bill eschewed complex flies that tried too hard to imitate or attract. This was “cheating” in his books. I think, for him the fly was merely a tool, an extension of the fisher. He was, in many ways, the quintessential Tenkara fisherman, long before “Tenkara” became a thing.

I suppose that’s how he lived his life too. He fished hard and often and lived as simply as one should. He revered God. He Loved his family. He embraced life, and he simply lived it to its full.

Brett Coombes

August 2025