I lay in bed this morning, as the rain pattered on the roof, thinking as one does, about exactly where to spread our “winnings”. We have all, I am sure day- dreamed about how exactly we would spend our lottery winnings. A new truck, a couple of bamboo fly rods, a few trips to exotic fly-fishing locations reachable only by helicopter: Kamkatchka. New Zealand. Alaska. Maybe Mongolia for Taimen. That sort of thing. But our winnings this time are real winnings. They are Trout. Hatched Trout, and thousands of them.

Thousands of them!

We had a good year at the hatchery this year you see, and we have a last batch of some twenty odd thousand fry, that need to go into the dams tomorrow.

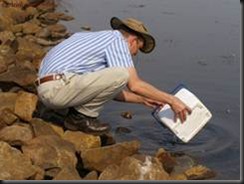

We don’t have any means of feeding our progeny, so when this time comes, two weeks or so after hatching, the alevins have absorbed their yolk sacks, and are swimming to the top of the tanks, and starting to look for food. Time is of the essence. The little buggers are crowded and hungry, and every day counts. We have to get them out into the big bad world of wild Trout: the open water. There is no time to waste. We need to net them out, place them in thick plastic bags filled with water, and go off around the farm stocking our various dams.

Off on a stocking round

And that is where the early morning deliberation comes in: where to stock them? The spreadsheets have been updated, the prior stocking has been entered, and the demographics graphs reviewed to make sure nothing is skewed. Granted, one cannot possibly count out seventy thousand minute alevins, so we make a gallant effort to estimate the numbers, using the very loose, but confidently quoted unit of measure of “a cool box”. “A cool box” is just that, a standard Coleman’s cool box. Either filled with water, or filled with two large bags of water, and in turn stocked with Alevins to a density “kind of like that”. Sort of covering half of the floor of the cool box when one looks in from above. Roughly. And that is about a thousand fish. Maybe fifteen hundred.

“A cool box” of alevins

On the other side of the equation we do at least know the exact size of the various dams. Thinking about it, that is perhaps all we do know for sure, because the next big guess is the survival rates of these little blighters. We know they die in droves, but what percentage is that, and working back from there, how many cool boxes are enough? We don’t know.

I do run a lovely spreadsheet, as I have mentioned, in which we try to model the success or otherwise of the stocking. It is a very iterative thing, but a lot of fun, and it’s upkeep and the associated tinkering occupies many happy hours. We guess at what we put in as best we can. Then we guess at a mortality rate. We know that we do better when stocking into the feeder stream, and not straight into the impoundment of water itself. That requires good flow in winter, so by implication, the heavier the snows, or the wetter the autumn, the better. That is one thing we do know.

The other thing we know, is that the more spread out the stocking, the better. By that I cover three distinct topics. Firstly, if PD and I stock three dams, splitting the fish in proportion to dam size as best we can, and Paul does the same later the next day, followed by Bruce the following week end, we surely have a better chance of getting the proportions right. Surely , if you believe in the law of averages, as we must do. Secondly, if that first stocking was made under the watchful eye of a Galunkie, or a kingfisher on the overhead line above, the batch may have been decimated as the bakkie disappeared over the hill. And hence, by having two other batches go in, on days that the Galunkie was half asleep, we have improved the chances. And lastly, there is the obvious concept of spreading the stocking out geographically. Some here, some there. All along the dam wall amongst the rocks, where there are nooks and crannies for protection. Up and down the stream, across in the reeds. That sort of thing.

In the nooks and crannies

And in the final analysis, we just see how the fishing goes. If it is poorer than we hoped, I open the spreadsheet up one arbitrary Tuesday and replace the “10%” survival figure with a “7”. As the following season unfolds, and we are talking eighteen months after the stocking here, I might go back and make it a “5”, or hopefully re-evaluate and change it to a “15%”. This is all very subjective, but what does emerge over the next five years (being the lifespan of your average Rainbow Trout), is a model that explains to some degree why you caught a lot of two pounders in that year, and none in the following year for example.

We also know that a virgin dam , one that has been without fish, does very well in the first year or two. So if we have a water that has fished particularly badly for a year or two, we might consider it a “virtual virgin”, and stock it a little heavier, knowing that it should have plenty of food for a bit of an over-stocking . On the converse, a dam might have a very productive year, and either the fish are a little thinner than they might have been, or, they could get a little thinner, if you were to introduce more hungry mouths into the same body of water. This is quite beside the fact that all those hungry mouths from last year’s successful stocking may be opening up for some tasty alevins. So in this case we might tap off just a little with the stocking rate.

One thing is for sure, and that is that things go in cycles. We know that three seasons back the dam on the hill, was the place to go for easy pickings. That two years ago the old dam produced a crop of hogs like never before, and that neither of these events will repeat themselves in the following year. That is a certainty!

So what do we take from this? Well, I take from it that fishing is a fickle thing, and that one has to roll with the good times, and tolerate the bad. Dams will have off years. Maybe “off patches” lasting three seasons or more. One can react to this with a certain amount of frothing and squealing, or you can, calmly take your rod down and drive over the hill to the other dam, to see what is up, over there. In fact as I grow older, I am even less inclined to do that. All that rushing from one dam to another, taking rods down and putting them up again, gets to seem a little more like a shopping trip to a busy mall than a day in the country. So I am just a little more inclined to light up my gas stove, and make a fresh cup of coffee beside the dam, as part of the ritual of waiting out the so called “bad times” . Perhaps I will pick up the camera and go looking for the Stanley Bustard.

Stanley Bustard

Or better still, put on the polarising filter, and walk to the top of the hill overlooking the dam, to see if I can re-memorise the position of the old river channel, or see where the weeds beds have shifted to, for future expedition planning purposes.

We seem to accept that rivers will have off patches for months. We know that there will be droughts and floods, and infestations of bramble. Whole seasons lost. A river fisherman accepts these with some grace and calm. He looks back over his photos and remembers good seasons past, when the river had a spell in its prime, and he knows that those times will return. But on a piece of still water, I don’t think fishermen are as inclined to see the world of fly-fishing quite like that. I may be wrong, but I believe we have bred a generation of Stillwater fly-fishermen who have some set expectations of minimum success levels. Consistent success levels. Guys who record their fishing in what I see they call “sessions”. Like the first half and second half of a rugby game, with statistics per session, just like those that scroll across the bottom of the TV during a sports match. X number of hours, Y hatch, Z number of fish. It stands to reason that these guys don’t fish rivers a lot. Their figures would go to hell in a bad season, and some of their “sessions” would amount to walks in the country looking for holding water. Not the sort of thing that would appeal to them I don’t think. It is no wonder that our river beats are so seldom fished nowadays. Log books would look dismal.

Now don’t get me wrong. I keep a logbook. I have done for years, and I am quite fanatical about it all. But I am referring here to fisherman measuring success rate, and being driven by it. Keeping score. Selecting venues and weather in a particularly driven manner, with their eye on their catch rate. I suppose what I am describing is competitive angling. And I don’t like competitive angling. I don’t begrudge the guys who are into that sort of thing, but it is just not for me. Why: Because with your one eye on your catch rate, you probably won’t even see the Stanley Bustard. Because you will take the flask fishing instead of the stove, because it takes too long. Because you will drive over the hill to the next dam, and the next one, and the next one. And because when you have done that and you still haven’t caught the fish you wanted to, exactly what will your state of mind be? Content? I don’t think so.

Coffee break

So back to dreaming: where should we put this last top-up stocking of alevins. The house dam for sure: It hasn’t produced a fish in ages. It hasn’t been fished in ages. Those reeds are thick, and the weed growth has been prolific. But I slid the canoe in there this winter, and I saw the big hole of clear water that has opened up. And I know that others can’t see that from the shore, and that you can’t easily launch a float tube in those muddy margins.

Dale’s suffered an inversion this winter, and it looked first green and soapy, and then brown and soapy. It has been so good for a few years, but I wonder whether we shouldn’t give it a break, and let it flush clean and re-oxygenate this summer. We can start again next season. Let us not waste precious fish in there this year.

And then there is Roy’s. So small, and so weeded, that last year , and several others according to the records, we skipped stocking it. Now why did we do such a silly thing, I am thinking. I was up there last week, and it was looking so good.

A secret spot. Just add fish.

One Response