In recent years I have been re-reading some books on the topic of fishing the chalk streams and the limestone creeks (UK and USA respectively), and my attention was drawn to why these places were and are, such universities of flyfishing thought.

It relates to the fact that with the slow flow, unruffled surface, consistent water temperature, and clean water, they get regular and to some degree predicable hatches. It also relates to the fact that fish don’t have to expend a lot of energy to swim forward or up, to sip a miniscule fly. Added to that, the water chemistry (alkaline) is such that it produces a lot of bugs, and you can see everything happening.

With the laboratory set up, the observer just has to get into position, don a good peak hat and a pair of polarized glasses and watch the show. Of course the fish are spooky, so stalking them to watch is something to be done with care. Way back when, blinds were erected along the Letort spring creek in Pennsylvania for this purpose, and voila, the university was open.

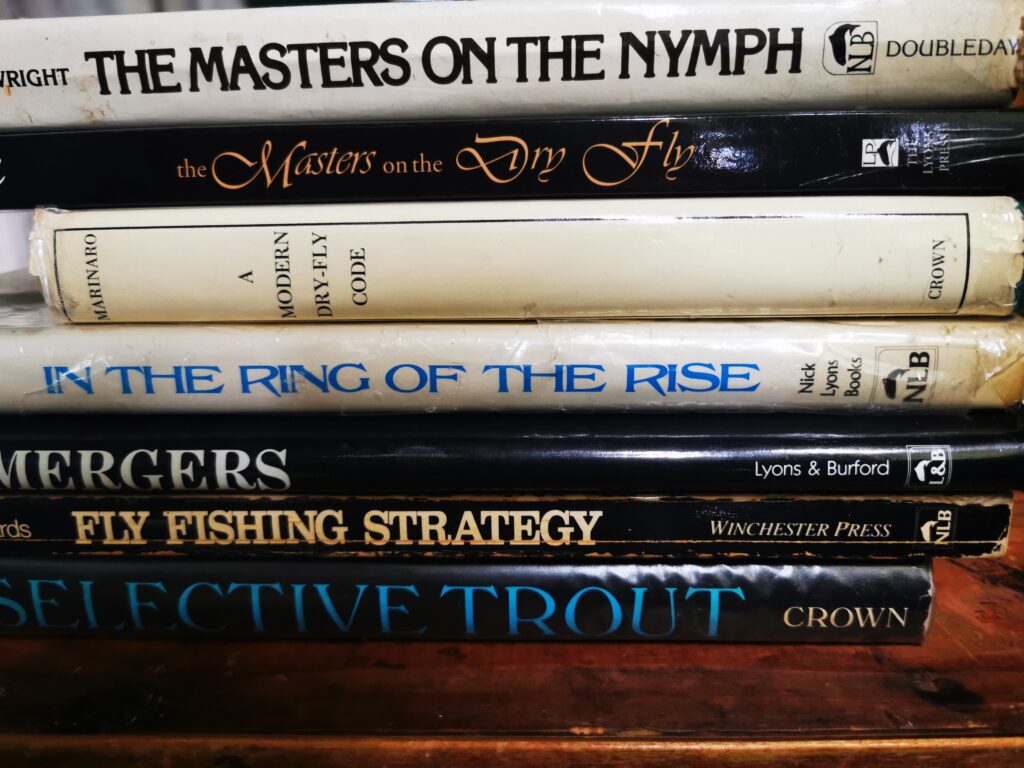

From that of course, spilled theories and photos and detailed analysis, that allowed us to recognize a rise-form typical of a trout eating a specific bug. That is because the professor in question could take a look at the bug a few feet away, drifting very slowly on the water. He could look with the naked eye, or a pair of binoculars or he could stroll down and net a few. Then, with the bug’s ID confirmed he could watch the fish taking them. How far was the fish prepared to move; what movements did it make to consume it, and so forth. Do you remember those photos in Goddard and Clark’s book, and the ones in “Ring of the Rise”?

When I entered the flyfishing world, Nick Lyons was at the peak of his career publishing flyfishing books, and there were people in my town who knew how to bust the political sanctions imposed by governments around the world against South Africa, to the extent that they could get those books.

We read them and took it all in.

Then we went fishing and tried to see what we were reading about, through the lens afforded us by those images and texts.

We were conducting that observation, both through inexperienced eyes, and on fast flowing freestone steams. Our streams were variously dirty, fast, acidic, drought affected and inhabited by fewer, smaller insects. The stuff we heard in the hotel meeting rooms and the slideshows we saw were mildly puzzling, because try as we may, we struggled to see these things when we were out on a piece of water.

To this day, I witness people pontificating about the exact shade of the caddisfly they have seen hatching in a particular location, looking for one, and not finding it, or anything else hatching, putting on a large Woolly Bugger and setting forth. Hell, I do that all the time. My own journal is littered with comments in the “hatches and feeding” box that say “couldn’t see any”, or “who knows what they were eating”. In recent months I have made myself a bug net and have been sampling some rapids, runs and glides. Something I have noticed is the couple of caddis pupae I have found, when I could see no hatch at all.

Be honest, have you ever seen a caddis pupa on a trout stream? Don’t feel bad, I hadn’t for decades, and for anyone who scoffs at that, take a look at the worst, fuzziest photo in any fishing book: It’s the photo of the caddis pupa!

Unless you have a bug net, and are lucky, you have very little chance of ever seeing one. Do you imitate them? Of course you do! So do I. Why? Because we read books, listen to experts and watch YouTube videos, that’s why.

So why can’t we do our own observation and learn from that, rather than from material coming from elsewhere.

There are a number of reasons. A big one is that we lack that consistency of ideal water conditions that I mentioned earlier. Our freestone streams oscillate between flood and drought, and have long periods of coloured water, or poor oxygenation, or high silt load. You can avoid that by going into the berg where the streams are cleaner, but the flow rates are just as variable, and always faster. Up in the berg you are on white water a lot of the time, and there fish either don’t grow big, or if they do, its not by eating thousands of tiny bugs in energy sapping flows. Go lower down to the meadow type water, and you have less ideal conditions, and in all cases our water is slightly acidic at best. And here the bigger Trout eat tadpoles, crabs, terrestrials and other large meaty, opportunistic meals, which give them more reward per unit of energy spent, than sipping minutiae.

So we don’t have consistent hatches. A small number of people have tried to develop hatch charts for my neck of the woods, but I haven’t seen an attempt at that in the last thirty years. I have seen a lot of Woolly Buggers thrown: a good number of them thrown by yours truly.

I use the term Woolly Buggers loosely of course. You can insert “Perdigon” or “PTN” or “something buggy” in there, the story is the same: we are not predicting, preparing for, and setting out to fish a hatch or even just a prevalence of a particular invertebrate species.

So, is this something to bemoan: The fact that we don’t have our own neat university of study, where we can crack the code in South Africa?

Not necessarily.

The way I see it, the lack of predictability introduces both a lot of postulating, theorizing and experimentation on the one hand, and a lot of excitement around hunting down opportunistic “purple patches ”,when it all comes together.

What do I mean by a purple patch? Let me define that in this context:

A Purple patch is when you encounter a prevalence, hatch or movement of one or more type of bug, imitate those bugs is size and form, and catch some fish that you might not otherwise have caught.

Some people would define a purple patch as a time when they caught heaps of fish. That doesn’t do it for me. I can catch dozens of fish on a generic nymph with a big silver bead on it, and I can enjoy that, but that is not what I am referring to here.

I write of “cracking the code”, and for me that is the holy grail. I actually despair when I catch fish after fish on successive trips, and have no idea why. The concept that a dark fly, or a white fly or a small fly “seems to be working today” has as much appeal to me as the notion of a beginner hitting a hole-in-one. So, soulless dredging with a pattern that seems to be working today is something that I get drawn into only through apathy. And a big fish caught that way, is on some level a bit of a let-down. I don’t want to catch a lunker because I was at the right place at the right time. I want to catch it because I worked it all out, hunted it and outsmarted it!

To be honest, that is something that seldom happens.

Add to that the fact that where I live, our number of flyfishers seems to be dwindling, to some degree at least due to emigration as people escape the chaos that is South Africa. Left behind is a small band of fly-fishers, and in turn only a small percentage of those pursue the type pf purple patch that I define above. How many fishermen are there in the KZN Midlands who will give up a string of fishing days to go hunting bugs, watching fish and taking notes and photos. What’s more, doing that on a challenging stream, with fewer fish where not many fishermen venture, is hardly an activity that competes with watching Curry Cup rugby.

It’s a lonely space I tell you!

But I recently saw a picture of a South African bloke in goggles getting into a pool to study the Trout. Ed Herbst leads the way in studying the stream, with his insightful Instagram posts. And the Letort Regulars in the USA and the likes of Sawyer and Goddard in the UK were oddities. They were outliers. They didn’t follow the crowd. They even chose some less popular waters, and they got inquisitive. I see a new book on South African aquatic invertebrates is due out soon.

I sniff an opportunity to start delving into our inconsistent conditions and attending the not so neat, not so consistent, University Of Purple.

4 Responses

Always enjoy your posts, and much of the above I might be inclined to agree with, but one thing that I learned is that the average UK chalk stream is flowing a good deal faster than you might imagine. Brisk walking pace at the slowest. The clarity, alkalinity etc make for a wonderful laboratory, but the speed makes me suspect that the fish are often not as selective as some pundits would have us believe. Keep up the good work..

Good point on the speed of flow Tim. I noticed a lot of fish on the Kennet and Test riding what I took to be a sort of “flow cushion” created by the weed, and springboarding from that they seemed to have a propensity to rise up through the column of flow more than I see here in KZN. Some Trout I watched on the Itchen (through the restaurant window while having breakfast!) were particularly remarkable in that they were in a really powerful flow, finning and feeding actively….. something I don’t see here at home. Trout behavior is such an intriguing subject, and a source of much enjoyable debate isn’t it!

I agree with your general sentiment but sadly the famous hatches of yore have become more sporadic and less intense on the chalkstreams, due to pollution I believe. I think this has made the trout slightly more generalist in their tastes. Thanks for an interesting piece.